“Know thyself and the MFA statistic in your Azure EntraID Tenant” cautioned the Oracle of Delphi.

I admit some artistic liberty was taken here, but like the ancient Greeks misreading cryptic prophecies, we overlook what’s closest – our own weaknesses, hiding in plain sight.

As you probably know, all most organizations with a cloud footprint use some kind of MFA to secure access to their online resources. Unfortunately, in my daily incident response work, I still see it not deployed, not enforced, broken, or “not-as-good-as-it-can-be.”

Introduction Link to heading

To be clear, whenever we talk about MFA, 2FA, or Multi-Factor-Authentication, we specifically mean Microsoft’s implementation of it in EntraID.

Microsoft is kind enough to document the supported MFA methods:

1| Method | Primary Authentication | Secondary Authentication |

2|--------------------------------------------|-------------------------|------------------------------|

3| Windows Hello for Business | Yes | MFA |

4| Microsoft Authenticator push | No | MFA and SSPR |

5| Microsoft Authenticator passwordless | Yes | No |

6| Microsoft Authenticator passkey | Yes | MFA |

7| Authenticator Lite | No | MFA |

8| Passkey (FIDO2) | Yes | MFA |

9| Certificate-based authentication (CBA) | Yes | MFA |

10| Hardware OATH tokens (preview) | No | MFA and SSPR |

11| Software OATH tokens | No | MFA and SSPR |

12| External authentication methods (preview) | No | MFA |

13| Temporary Access Pass (TAP) | Yes | MFA |

14| Text | Yes | MFA and SSPR |

15| Voice call | No | MFA and SSPR |

16| QR code (preview) | Yes | No |

17| Password | Yes | No |

While there is support for very strong, phishing-resistant methods like FIDO2 keys, others are less optimal — while still others are just-barely-better-than-nothing.

Case in point: SMS is still considered a valid candidate for Primary Authentication.

1| Method | Primary Authentication | Secondary Authentication |

2...

3| Text | Yes | MFA and SSPR |

4...

To be fair, it is absolutely possible (and advisable!) that you configure your Azure Tenant to have a robust posture when it comes to MFA and your login flows. Only because something is technically possible and supported does not mean that it should be used.

Still – I feel good standards have to be forced on users sometimes.

For instance, an attacker who has gained control of the password for a user account could repeatedly log in to a Microsoft endpoint like https://myaccount.microsoft.com and trigger a push notification to the end user’s device. This simple technique is known as MFA bombing — and it has cost people and businesses literally millions.

Oftentimes organizations don’t really know just how many of their users have which MFA methods defined, as they simply make an “enable / disable” decision at the tenant level and forget about it.

The more user-friendly methods like SMS, Voicemail, or E-Mail require little setup on the part of the end user, so insecure methods like these tend to dominate.

Before you know it, most users are only using a (hackable) private email address or a (SIM-swappable) phone number as their only MFA method.

I wanted to know just how good (or bad) the situation was so I threw together some Powershell to compute a statistic on which MFA methods were used by how many users.

Weak MFA methods == weak User Link to heading

When we check the available MFA options in our dev tenant, we decide to treat the Phone, Password and E-Mail methods as weak – not entirely without reason as there are well-known attacks against all three.

In our specific case, we define weak user as follows:

- has

weak MFA methodsconfigured (or none at all)

and

- is

not memberof a specialdeny group(see Note below)

For accounts that fit this pattern, an attacker with the right password could possibly:

-

log in directly to register their own MFA (if none other is set)

-

try to SIM-swap

-

MFA-bomb the user at 3AM

-

send them a phishing mail with an Evilginx payload

As I’m sure you are aware, they would all be defeated by a FIDO key (yay proper crypto 🙂!)

This obviously does not apply to every EntraID tenant — I will leave it to you to figure out what a weak user is in your tenant and adapt the script accordingly. Anyhow, those weak users are the ones we are most interested in.

Conditional Access based on EntraID Group

One way to deny an EntraID user access to your Cloud resources is to configure what is known as a Conditional Access (CA) Policy.

This policy can be configured based on many different properties, like the type of device the user is using, their location, the risk status of the user, and many others. A common technique to effectively deny access is to have a special EntraID group which, when a user is a member of, blocks access to every cloud resource.

Both the configuration of CA Policies and EntraID are out-of-scope for this writeup.

If you want the -deny option to work, you must be able to provide an EntraID group which blocks access for all its members.

Setup & Requirements Link to heading

You can grab the code from the GitHub repo here. To get the information we need, we are going to use some Powershell cmdlets which internally use the Microsoft Graph API.

To get more accurate data, the script filters the Get-MgUser() API call according to some more specifics that might not apply to everybody.

As an example, we are only interested in our own tenant and only care about enabled and synced users.

PS: Set the company name in StatusChecker.ps1

You will need atleast the following Entra permissions

Make sure you can execute Powershell and are allowed to call

Connect-MgGraphGet-MgUserGet-MgUserMemberOfGet-MgUserAuthenticationMethod

If you want to use the -deny option you will also need

Get-ADUserAdd-ADGroupMemberNameandGUIDof a “deny access” EntraID group

With all that said and done, it’s pretty much just a matter of

1PS:> .\StatusChecker.ps1

Results Link to heading

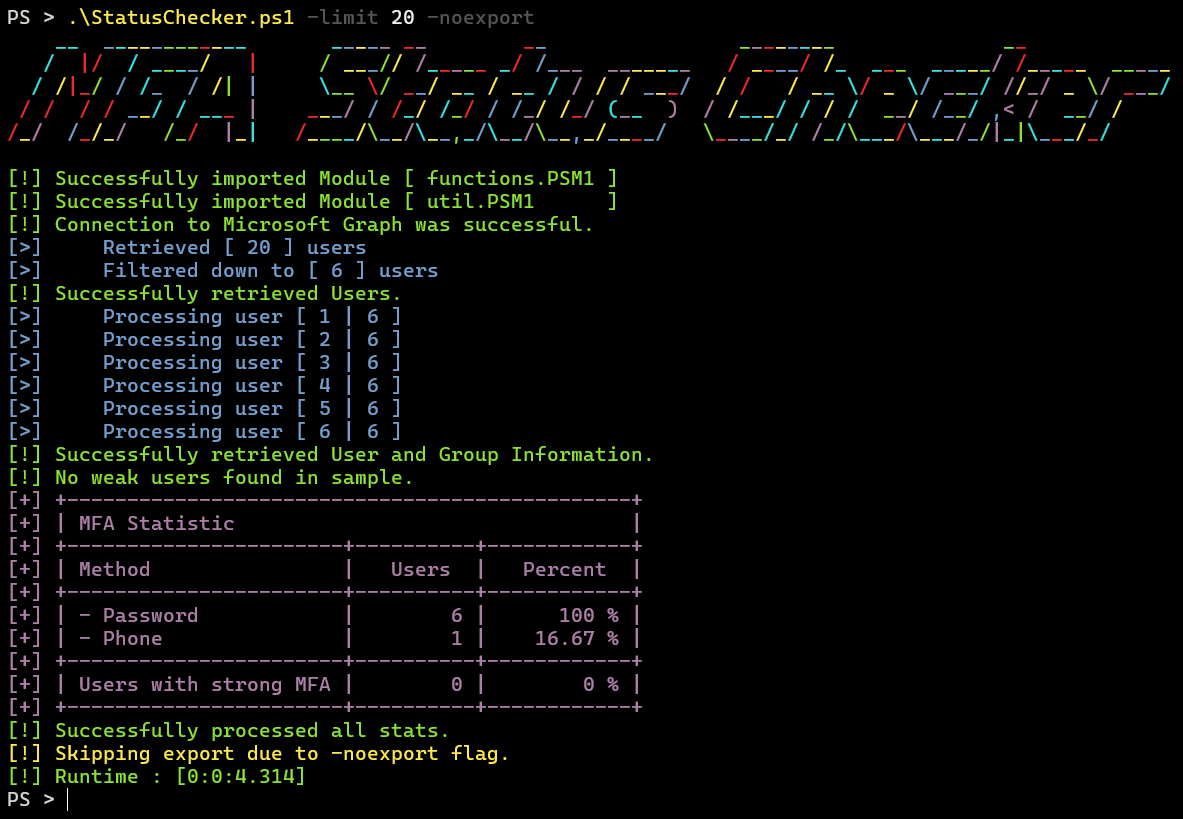

- we start with a small sample

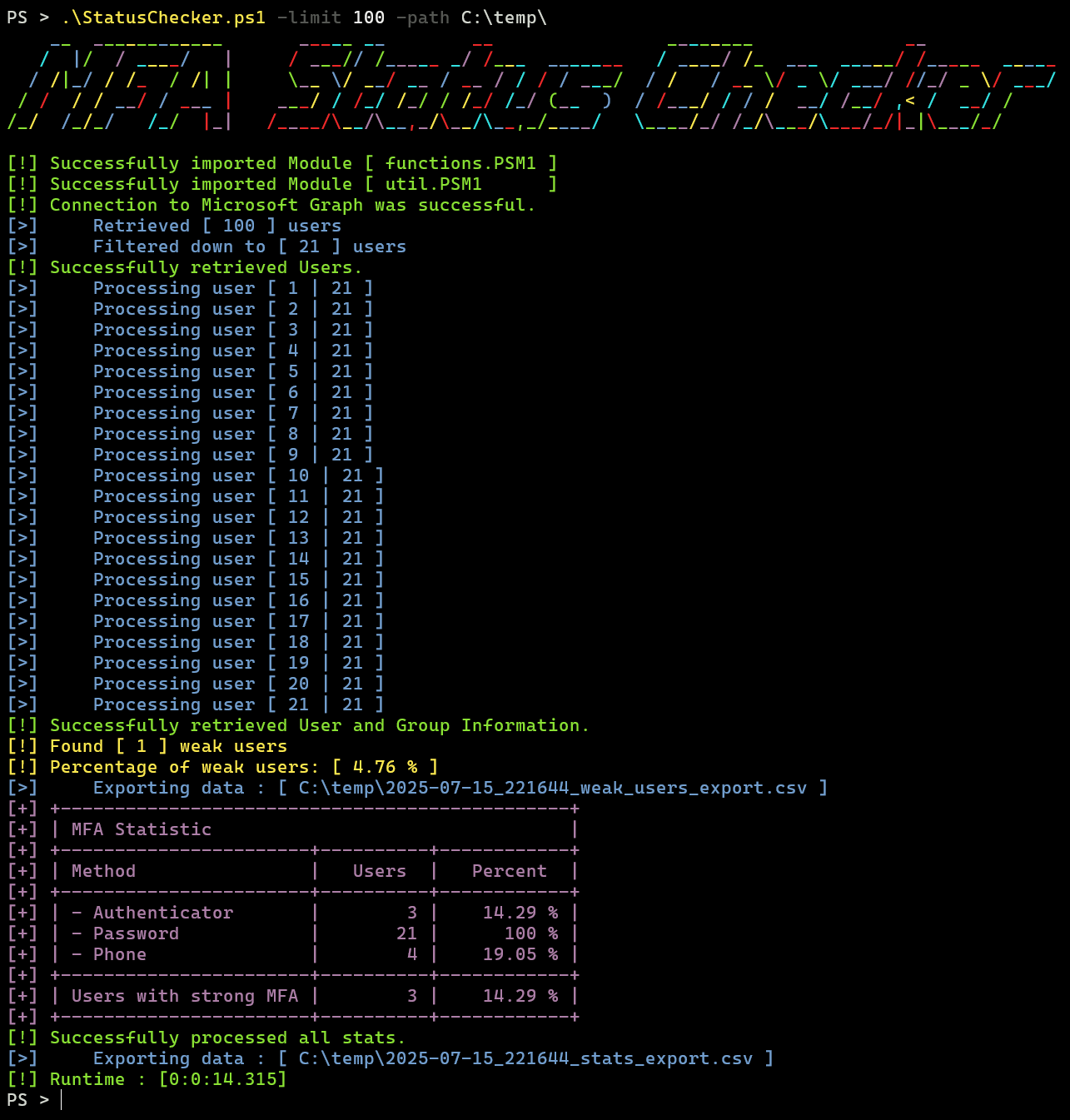

- we expand the scope and we find a vulnerable user

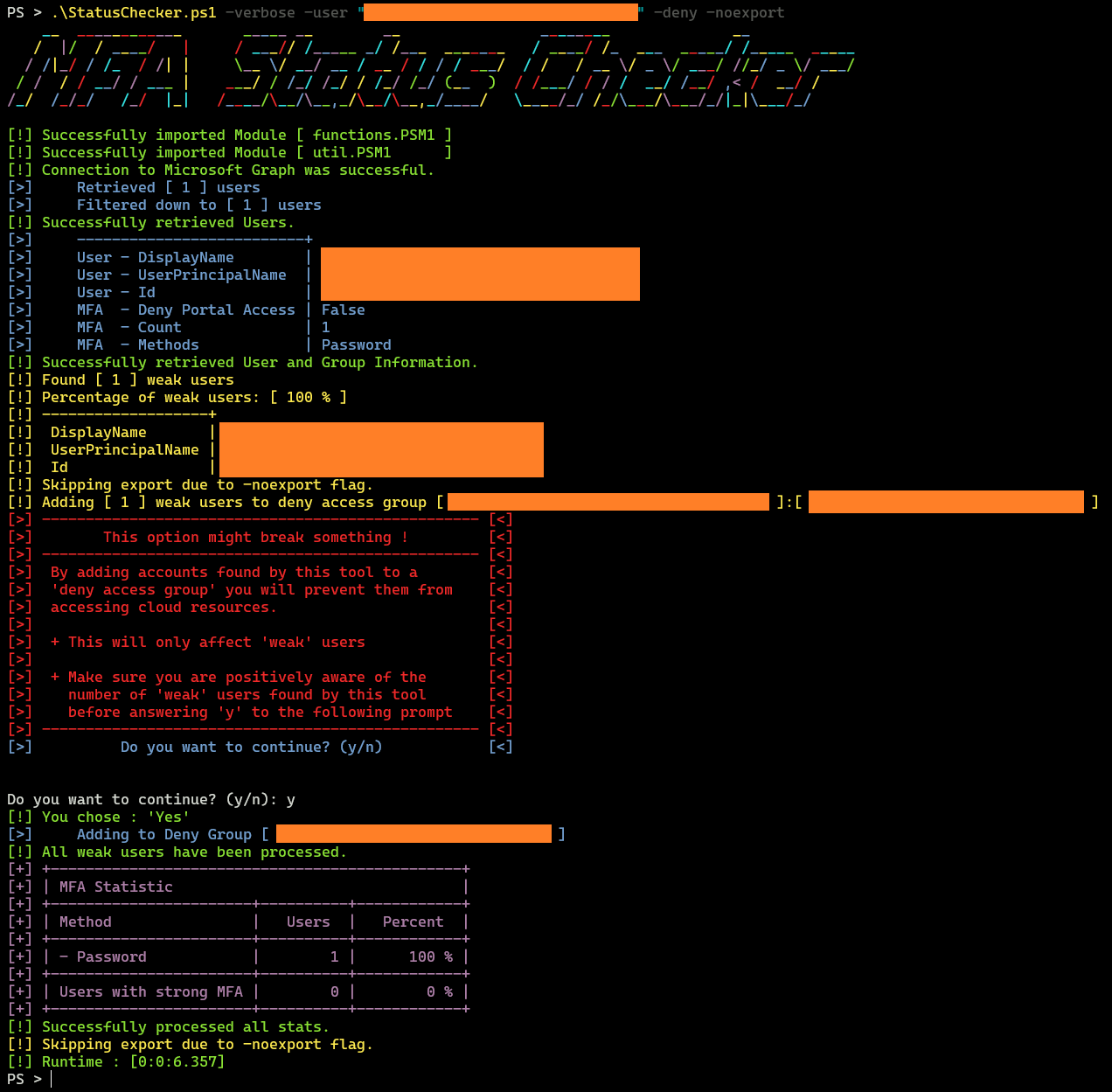

- we can deny them entry to the Tenant

Notes Link to heading

Figuring out what to do with this information is left for the reader.

Depending on your needs and context, this can range from:

-

requiring each user to re-register MFA and only allow strong auth methods

-

disabling users with weak MFA

-

(when doing a pentest) finding additional users to target 😈

Also you might want to think about automating this or using it as a starting point for a more elaborate toolkit that fits your needs.